Sex, lies and Hegel: did the intimate lives of philosophers shape their ideas?

Hugh Breakey, Griffith University

How did the intimate lives of major philosophers shape their ideas? Did their closest relationships with families, spouses, life partners and secret lovers influence their philosophies?

These are the questions Warren Ward sets out to answer in his new book, Lovers of Philosophy: How the Intimate Lives of Seven Philosophers Shaped Modern Thought.

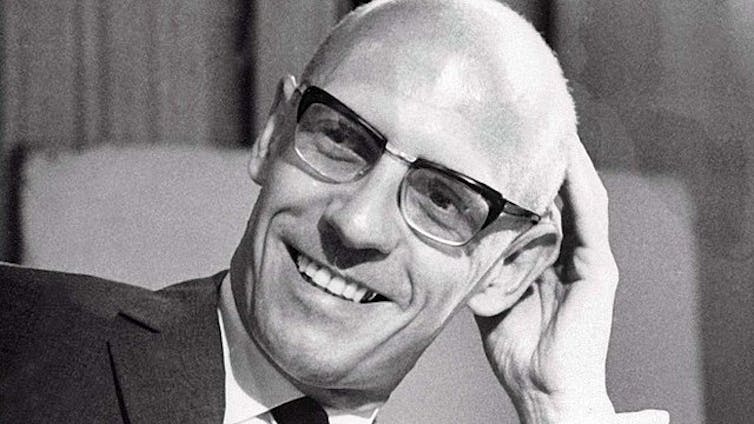

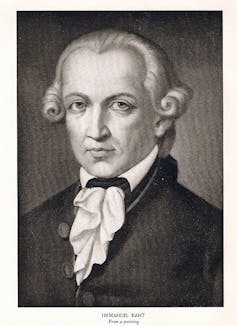

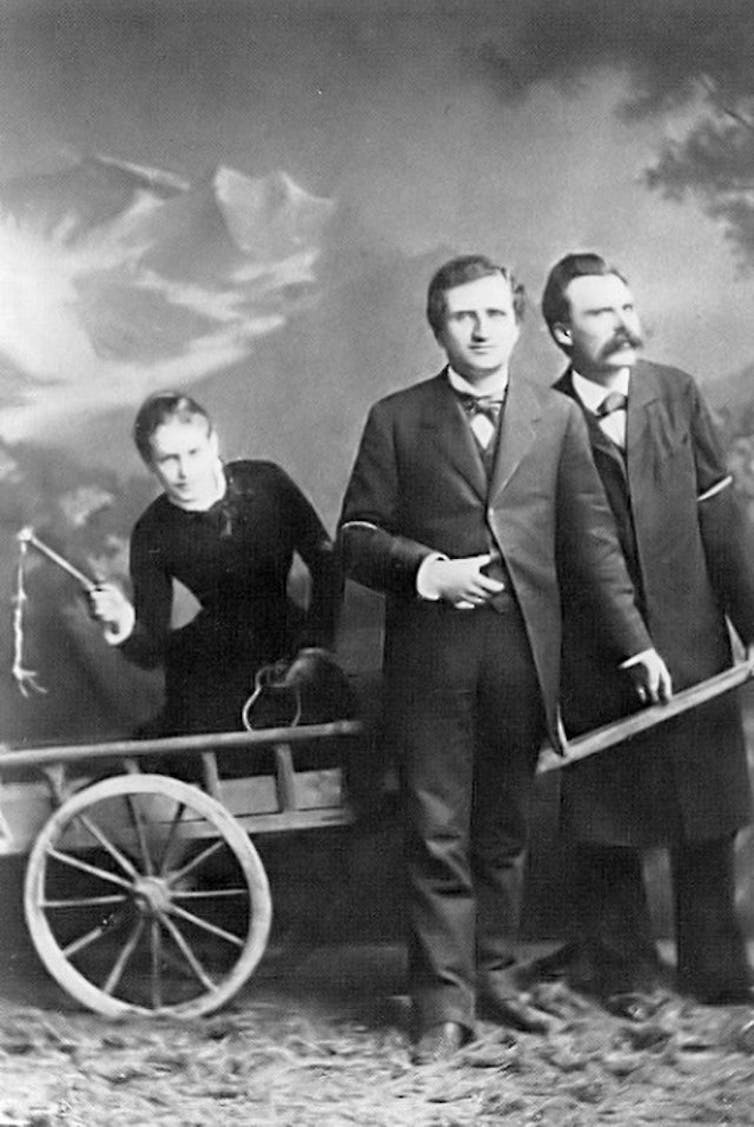

A psychiatrist and psychotherapist, Ward brings to his task both expertise and a passionate interest in his subjects. His canvas is continental philosophy from the Enlightenment to the late 20th century. He enters into the lives of this period’s most widely known philosophers: Kant, Hegel, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Sartre, Foucault and Derrida.

Review: Lovers of Philosophy: How the Intimate Lives of Seven Philosophers Shaped Modern Thought (Okham)

As well as exploring the connection between intimacy and philosophy, this book has another ambition. Ward recalls having been intimidated by the daunting authority of the philosophical greats. His perspective changed when he read Simone de Beauvoir’s autobiographical novel She Came to Stay (1943). Its unsparing portrayal of her lover Jean-Paul Sartre made the imposing philosopher seem more accessible.

Lovers of Philosophy similarly serves as a point of entry for all those who need reminding that philosophical giants are flawed and complex human beings, just like the rest of us.

An accessible and exciting history

Ward delivers on his ambitions. Filled with insight and more than a little excitement and intrigue, Lovers of Philosophy is enjoyably readable.

With dramatic flair, Ward recounts the excitement of the first meetings between the philosophers and their future lovers. He describes the consummation and growth of their relationships, and their experiences of devastating collapse and stinging rejection. While it is impossible to purge all scandal and salaciousness from such a work, Ward treats his subjects with dignity and thoughtfulness.

Philosophical events are brought to life too. Ward builds palpable tension as he enrols us into the bustling crowds awaiting Sartre’s famous public lecture, “Existentialism is a Humanism”. We are led discreetly into a hushed hall to witness Foucault’s scintillating defence of his thesis under searching cross-examination.

Ward’s psychological insights are thoughtful and commonsense. If anything, a little more psychological theorising might have been welcome. After all, many of the philosophers he discusses — Nietzsche and Foucault, in particular — left their marks on psychiatry. It’s intriguing to reflect on the possibility of their own insights being turned back on them.

The penetration of Ward’s psychoanalysis increases appreciably as we move forward in time. The historical records about the lives of Sartre, de Beauvoir, Foucault and Derrida are more detailed than those of earlier thinkers, so Ward is able to speak with greater confidence and nuance.

The book’s focus, like the philosophical canon itself, is weighted towards men. Yet the intellectual heft of philosophical women permeates the book. This is most explicit in the cases of Hannah Arendt and Simone de Beauvoir. These two philosophers’ lives and loves are explored in detail, and not merely with reference to their relationships with Heidegger and Sartre respectively.

This intellectual heft is also apparent in Ward’s discussion of the influence of lesser known figures who acted as confidants and discussants, such as the essayist and artist Countess Caroline von Keyserlingk (for Kant) and the Russian-born psychotherapist Lou Salome (for Nietzsche).

Ward’s book is not too heavy on philosophy. It keeps a strong focus on families, lovers and life partners. It also registers the tumult of disease, revolution and war that ravaged Europe throughout this period. There is typically around a generation between each of the figures Ward studies, allowing each chapter to pick up, biographically and philosophically, where the last one left off.

Ward does, however, provide accessible overviews of his philosophers’ main theoretical ideas, often using their own words to explain their perspectives. This provides enough philosophical grist to consider the ways that the philosophers’ conflicts and passions might have influenced their ideas, though there are a few moments when Ward’s discussion is a little off-beam.

It would have been a surprise to Kant, for example, and even more to his predecessors Thomas Hobbes and David Hume, to discover that he intended to craft the first purely secular moral philosophy since Hellenistic times.

Humanising the canon

There is much to be learned from Ward’s insightful journey through the history of philosophy. His study helpfully reminds us that, although these august figures became authorities whose names are invoked in respectful tones, their authority was hard won.

All the philosophers he examines had revolutionary ideas. They were trying to step outside assumptions and perspectives that had held sway for centuries, or even millennia. Being a “great” philosopher necessarily requires introducing something genuinely original, or questioning ideas that have not been questioned.

The road of a philosophical revolutionary is hard and difficult, but Ward’s biographies provide an enjoyable series of “rags to riches” stories. They chart each philosopher’s journey from heresy or irrelevance to philosophical and often popular acclaim (with the notable exception of Nietzsche, who received little acclaim in his own lifetime).

Apprehending the often difficult lives of philosophers, the work and sacrifice they poured into their philosophy, and the personal struggles that left an imprint on their thinking can serve to make the reader a little more sympathetic to their ideas.

Many of Ward’s philosophers lived through hard times. In Kant’s and Hegel’s families, almost half the children did not make it to maturity. The early deaths of beloved parents is a consistent refrain.

Understanding these challenges and sacrifices makes it easier to appreciate how counter-intuitive and even radical ideas may have made sense to their authors, given their situations in life and the personal histories that had led them there.

The dark side of dreamers

There is no escaping that these esteemed philosophers had their sinister sides. Ward’s exploration of their intimate relationships exposes unsavoury aspects of their personalities, sometimes to the point where this challenges how we should think of their work.

Many of their personal decisions were scandalous in their own time and look even more shocking to the modern eye. In addition to the many infidelities, there are multiple trysts between teachers and students (Heidegger and Arendt, de Beauvoir and Olga Kosakiewicz, Foucault and Daniel Defert.

There was even impropriety between therapist and patient. Late in his life, Sartre started performing a new type of psychotherapy, basing the treatment on his existentialist philosophy. He quickly took one of his new clients, 19-year-old Arlette Elkaim, as a lover. Soon after, in a strange twist, he legally adopted her as his daughter.

The reader is forced to face up to Hegel’s harrowing refusal to honour his promise to marry the mother of his illegitimate son, leaving her alone and destitute, and consigning his son to the miseries of an orphanage. Both were ultimately to die in tragic circumstances.

There is also the problem of Heidegger’s appalling anti-Semitism, to say nothing of his Nazi party membership. Derrida and Sartre could be sinister in their pursuit of sexual conquests. There is little evidence in any of this that moralising philosophers are ethically better than anyone else.

Nietzsche and Kant stand somewhat apart from this indictment, though in different ways. Kant’s intimate life is roughly what one would expect from the author of the Categorical Imperative. Apart from a curious period of midlife listlessness, during which he frequented billiard halls and card-playing dens, Kant behaved in his intimate relations with dignity and conscientiousness. In fact, his carefulness and procrastination in matters of the heart seem almost stereotypical.

Nietzsche is different again. Strikingly, given the explicit misogyny in his published works, there appears to be little that is objectionable about his private treatment of women. Rather than failing in his personal life to live up to the high standards of his ethical philosophy, the self-declared “immoralist” invites the opposite complaint.

He failed to voice in his philosophy the respect he showed in his life to the two extraordinary, free-spirited and fiercely intelligent women who, at different times, captured his heart: Cosima von Bulow (Richard Wagner’s lover and later wife) and the trailblazing psychologist Lou Salome.

The impact of private life on philosophical ideas

There is both scholarly danger and intellectual promise in Ward’s project of tracing the influence of intimate lives on philosophical thought.

The danger parallels the challenges that arise when tracing one philosophical work’s influence on a subsequent work. As the philosopher Quentin Skinner has pointed out, it is all too easy to find points of contact between one philosophical system and another.

Philosophical systems, often developed over lifetimes and delivered through publications, speeches and discussions are rich, dynamic, nuanced and often slightly contradictory intellectual creations. This means there will always be overlaps and resemblances from one system and another. We must be wary of making too much of these similarities.

The same point may be made about exploring the intersection between human lives and philosophical theories. A human life, from start to finish, is as rich, dynamic, nuanced and contradictory as any philosophical system. All humans have their complex biographies and journeys, their families and relationships, their secrets and intrigues, their unique psychologies and thoughts. They are all influenced by the reigning culture’s ideas, language and practices.

When we map a human life onto a philosophical system, we will inevitably find enticing parallels. It may well be that the conflict in Hegel’s personal life helped spur his dialectical idealism.

Perhaps the raw sense of something important dying within Nietzsche in the wake of his rejection by Lou Salome drove him to pen his famous declaration that “God is Dead!”

Perhaps the shifting notions of identity (French, Algerian, American, Jew) that dominated Derrida’s early life might have driven his later insights on the importance, but also the plasticity, of language and its construction. Equally though, these overlaps might be merely coincidental. Confirmation bias is an ever-present risk.

The streetlight effect

Yet we must not be too quick to brush aside explorations like Ward’s, for there is another cognitive bias lurking here, which is sometimes termed the “streetlight effect”.

The name is derived from a quaint parable about a drunk man looking for his keys under a streetlight. A police officer comes along and helps, but when they fail to find the keys, the officer asks if the man is sure he lost them here. The man replies that he lost the keys in the nearby park. When the officer asks why he is looking for them here, the man answers: because this is where the light is.

When we search for the influences that helped to create groundbreaking philosophical works, we can try to avoid speculation by focusing on tangibles and verifiable facts: that their scholarly mentor was such-and-such, or that they were known to have read so-and-so. This approach lets us invoke hard evidence.

The worry is that we work here because this is where the light is. Less knowable is what happens behind closed doors and in secret whispers. The philosophical consequences of passions, betrayals and trysts are much harder to discern.

Ward’s explorations hammer home that it is altogether possible that these experiences leave the most telling psychological marks. The things that exert the most profound influence are often our families, our loves and our most intimate friends. Yet it is to his credit that Ward explicitly invites us to “wonder” and “speculate” at key junctures, cautioning us even as he cultivates the fertile terrain between psychology and philosophy.

Grave life costs

What, then, do we learn from this rich and thrilling history of philosophy and lived intimacy?

One repeated lesson is that new philosophical systems require solitary work. All of Ward’s philosophers shared the joys of philosophical discussion, but equally their writing required enormous swathes of time spent on their own.

Kant cut off almost all social engagements during a “silent decade” of intense study from 1771 to 1780, where he formulated his world-changing philosophical ideas. Heidegger would isolate himself in die Hütte (“the Hut”): a cabin in the dark German forest, almost cut off from the outside world.

In their own ways, all of Ward’s philosophers had times when they had to become, as Nietzsche put it, “born, sworn jealous friends of solitude”.

Sometimes this solitude was healthily interspersed with human contact. Sartre and de Beauvoir’s lunchtime discussions were bookended by their solitary morning and afternoon writing sessions. But all too often there were grave life costs. Partners and wives were left alone and ignored as philosophical ambitions were pursued.

Indeed, there could be psychological costs to the philosophical life. Ward rightly speaks of philosophers being consumed by their work. Often, this is in a good way: they are driven by a deeper calling that gives their lives meaning.

But the labours of philosophical creation demanded effort, isolation, sacrifice, and even risks of poverty. Hypochondria was far from uncommon. Lou Salome’s sickness and fainting spells, driven by her obsessive learning, recalls David Hume’s sufferings from the “disease of the learned”.

Yet philosophy was enriching and fulfilling too, sometimes driving the scholars to seek human connection in their world. Almost all found a trusted partner that they could speak with and who would enrich and challenge their thinking. Even during his “silent decade”, Kant regularly met his two prized friends, Joseph Green and the Countess von Keyserlingk, for philosophical discussion.

Sheer sexiness

One final point warrants emphasis, as strange as it must sound to those who find philosophy dry and abstract: the sheer sexiness of the philosophical encounter.

Throughout many of Ward’s vignettes, the descent into deep philosophical discussion with a respected peer, especially when that peer is a potential romantic partner, turns out to be as erotically charged as it is intellectually exciting.

There are many potential forces at work here pushing two minds into intimate connection. There is the playful jousting, the recognition of being seen for one’s deepest thoughts and honoured for one’s intelligence and erudition, the hypnotic flow of genuine listening and the awareness of being truly heard, the meeting of the minds and the shared intellectual creation that is philosophical argument, the heady frisson of questioning the unquestionable, and the wonder of seeing one’s ideas take root in another’s deepest psyche.

Alas, the erotic edge here is not innocent in the lives of these philosophers. While it did sometimes occur between equals — between Nietzsche and Salome, Sartre and de Beauvoir — it very often arose between unequals and in ways that shattered existing intimate relationships.

This, then, is the image with which Ward leaves us on his closing pages, as he completes his visit to the École normale supérieure in Paris, where the paths of de Beauvoir and Sartre first crossed. There he spies two students, a young man and woman, not yet lovers, but consumed in conversation, being drawn ever-deeper into the dance of each other’s ideas.

Arguably, this is the great contribution of Ward’s book. It purges us of what Derrida bemoaned as the carefully crafted presentation of the philosopher as asexual, standing forever apart.

In Lovers of Philosophy, philosophers come to us in their full richness. They are lifelong spouses, warm friends and secret lovers, as much as they are careful scholars, dazzling thinkers and imposing authorities.

Hugh Breakey, Deputy Director, Institute for Ethics, Governance & Law. President, Australian Association for Professional & Applied Ethics., Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.